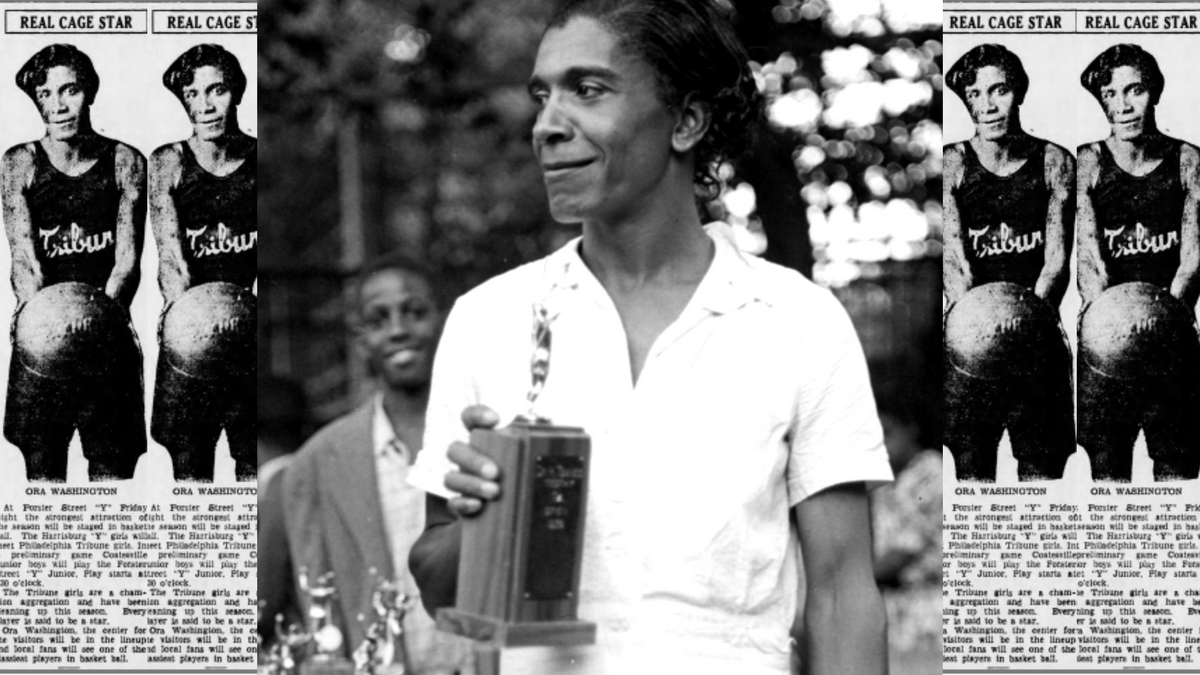

Ora Washington

Ora Washington (1898-1971) is considered America’s first Black woman sports celebrity.

Photo: Harrisburg Telegraph newsclip from March 19, 1936 and Ora after winning the 1939 Pennsylvania Open on July 30, 1939. (John W. Mosely, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Ora Washington (1898-1971) is considered America’s first Black woman sports celebrity. Dubbed “Queen Ora” or “The Queen of the Courts,” Washington dominated in both tennis and basketball.

She could also be called the Queen of Dominance.

On the tennis court, Washington won 12-straight American Tennis Association doubles titles and nine-straight singles titles. The ATA was founded in 1916 after what is now the United States Tennis Association banned Black players from its competitions.

On the basketball court, Washington won 11 consecutive world titles and played for the Philadelphia Tribunes and Germantown Hornets. At 5’7, Washington played center, could shoot with both hands, got steals and was considered an all-around player.

She entered the Black Athletes Hall of Fame in 1976, was enshrined in the Temple Sports Hall of Fame, Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame and Naismith Hall of Fame.

Washington was presented into the Naismith in 2018 by fellow Philly legend Dawn Staley, in the same class as Tina Thompson.

Washington passed away in 1971; there was a Philadelphia Tribune obituary, but most of the sports world hadn’t known. After retiring, she’d been working as a housekeeper, just as she’d been throughout her sports career.

Subscribe now to The Black Sportswoman.

If you google Queen Ora now, there are plenty of profiles (linked below) of Washington. But many include words like “nearly forgotten” and “relegated to the footnotes of history.”

If her dominance was chronicled in the Black press, why did it take so much effort from people like people like Pamela Grundy and Claude Johnson for her to be remembered?

For reference, Washington played against, trained with and mentored Althea Gibson, who is better known, in direct comparison, and who “broke the color line” in tennis and became the first African American to win a Grand Slam title in 1956 before winning Wimbledon and US Nationals in 1958 and 1959. Washington won her last title in 1947.

There doesn’t seem to be one answer. But many factors may have contributed to Washington being “forgotten.”

Washington thrived during a time where competitive sports in general – and especially basketball – were considered frowned upon for women.

Claude Johnson wrote, “Starting in the 1920s, sports educators and authorities began a systematic effort to curtail female hoops. In 1923, the Women’s Division of the National Amateur Athletic Federation launched a campaign against women’s competition in high schools and colleges as well as in the Olympic Games, under the leadership of Lou Henry Hoover,” who also led the Girls Scouts.

Opponents of competition claimed it hurt women’s bodies and reproductive organs, but there was an aspect of respectability at play, including what classified a “lady.”

Dictionary.com defines respectability politics as: a set of beliefs holding that conformity to prescribed mainstream standards of appearance and behavior will protect a person who is part of a marginalized group, especially a Black person, from prejudices and systemic injustices.

While white women like Helen Wills Moody refused to play against her, Washington was also criticized by her Black opponents.

The 1930s series between the Philadelphia Tribunes and Bennett College was a historic matchup between two dominant teams during a time where most institutions were cancelling their women’s basketball programs.

But Lucille Townsend of Bennett College said Washington, “looked like the worst ruffian you ever wanted to see. She looked like she’d been out pickin’ cotton all day, shavin’ hogs, and everything else.”

In the article titled We Were Ladies, We Just Played Basketball Like Boys, Rita Liberti writes, “Washington’s rugged appearance stood in opposition of the feminine ideals that Townsend and other black college educated women were trained to regard as “earmarks of a lady.”

Washington “formed her closest relationships with other women,” and didn’t conform to mainstream ideals of what a woman should be, look like or do. “In truth,” writes Jennifer H. Lansbury, “it seemed that the criticisms laid at Washington’s feet had more to do with her physical presence than her abilities as a sportswoman.”

Former Philadelphia Tribune reporter Len Lear says Washington “didn’t have anger about the race issue” but one thing no one was allowed to disrespect was her talent.

Washington came out of retirement in 1939 to compete against Flora Lomax, the new “glamour girl of tennis,” because people assumed Washington left the game out of fear of playing Lomax.

“They said Ora was not so good any more,” Washington told Harry Webber of the Baltimore Afro American. “I had not planned to enter singles this year, but I just had to go up to Buffalo to prove somebody was wrong.”

For your personal library:

A Spectacular Leap by Jennifer H. Lansbury

Read more online:

Pamela Grundy: In Search of Ora Washington

Trailblazer Ora Mae Washington should be in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

Before Althea Gibson, there was Ora Washington

The Nearly Forgotten History Of Basketball HOF Inductee Ora Washington

Queen of the Courts: How Ora Washington Helped Philly ‘Forget the Depression’

Dual-Sport Trailblazer Ora Washington Gets Her Due in Basketball Hall of Fame

Watch Later:

Comments ()